Have you noticed lately that your grass feels spongy underfoot? Or are yellow patches popping up everywhere in your yard? It may be a sign that your lawn has too much thatch.

Some thatch in your lawn can be healthy for your yard, but too much thatch will result in bare patches, lawn diseases, or spongy turf. Learn what signs to look for so that you can take action if your yard is suffering from an abundance of thatch.

Here are five signs to keep a lookout for. If you notice one or more of these symptoms, your turf might be telling you it’s time to dethatch your lawn.

1. Your Turf Feels Spongy

A healthy thatch level (half an inch or less) gives your grass a soft, bouncy feeling underfoot. But if things start to feel overly squishy, it could signal your thatch is too thick.

When this happens, your lawn can hold on to too much water like a sponge, making things (like lawn mowers) more apt to sink into the ground (e.g., your lawn mower won’t be level and can accidentally cut your lawn too short).

See Related:

2. Your Lawn is Suffering From Diseases or Pests

Thick thatch provides an ample buffet for bugs to feed on and creates a desirable habitat for fungi and other diseases to thrive — think pests like grubs or chinch bugs or common lawn diseases like brown patch or pythium blight. These can cause your grass to turn brown, wilt, and/or become excessively dry.

Note: Another signal you have thick lawn thatch is if fungicides, pesticides, and herbicides aren’t working properly in your lawn. Often, these treatments can get stuck in the thatch, rather than making their way through the soil, and thus, cannot address the problems.

See Related:

- Lawn Grubs: How and When to Kill Them

- How to Identify, Control, and Prevent Brown Patch

- How to Identify, Control, and Prevent Pythium Blight Lawn Disease

3. Thatch is More Than One-Half-Inch Thick

More than one-half inch of thatch can block sun, water, and other nutrients from reaching turf roots and cause roots to become shallow, taking up space within the thatch layer, rather than growing deep into the soil.

If the layer is thin (one-half inch or less), your lawn is in good shape and doesn’t need dethatching.

To check your lawn’s layer of thatch: Cut out a 2- to 3-inch segment of turf with a trowel or grass plugger, and measure the thickness of the existing thatch.

4. Yellow, Browning, or Bare Turf

When you see bare patches or dying grass, it could be an indication of a lawn that needs dethatching.

Despite your best efforts to fertilize, overseed, and aerate, you may have a thatch problem if bare spots persist. Thick thatch can lead to bare or browning or yellow spots simply because it blocks necessary nutrients from reaching turf roots.

In turn, grass roots will start growing within the layer of thatch, which will predispose the plants to stress (and death) from drought, heat, and overwatering.

5. Thatch is Visible

Sometimes the thatch layer can get so high that eventually you will be able to see it rising above your grass line.

By that point, you won’t even have to measure your thatch level because it will be clear that your thatch is too thick. When that much thatch has accumulated on your lawn, it will start to choke out the healthy grass.

Once you have determined that your lawn has too much thatch, you should fix the problem by dethatching your lawn.

See Related:

FAQ About Thatch in Your Lawn

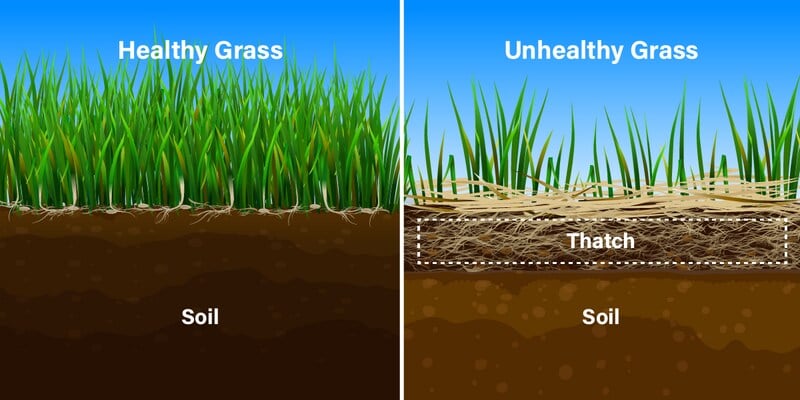

The thatch in your lawn is a layer of organic matter composed of living, dead, and decaying grass stems, crowns, and roots.

What does thatch look like? Thatch looks like a layer of brown or gray stringy plant matter located between the soil and grass stems.

See Related:

• What is Thatch in Your Lawn?

Grass types that spread via stolons or rhizomes (types of stems) are prone to excessive thatch.

Why? Rhizomes or stolons take longer to break down during decomposition. But bunching grasses, like tall fescue and perennial ryegrass, spread via tillers, so there typically isn’t an abundance of stems.

Plan to dethatch your lawn about once a year if you are growing these cool-season grasses, which are grass types that grow best in cooler climates:

• Creeping red fescue

• Creeping bentgrass

• Kentucky bluegrass

You will also have to dethatch annually if you have any of these warm-season grasses, which are common in warmer climates:

• Bermudagrass

• St. Augustinegrass

• Centipedegrass

• Zoysiagrass

Which grass type do you have? Cool-season grasses are popular in the northern U.S., and warm-season grasses are common in the warmer southern states. In the middle states, you can find both.

Using a dethatching machine is the best way to remove thatch. You can hire a professional to dethatch your yard, or you can dethatch your lawn yourself using a vertical mower, also known as a power rake. To dethatch your lawn manually, use a thatch rake to rake the thatch out of your lawn.

Out of all the pros and cons of dethatching your lawn, the work involved in renting a machine is one of the few cons. Renting professional equipment can be cumbersome, expensive, and may require a truck or trailer to haul it back and forth. But here’s a solution: There are now inexpensive, lightweight models you can buy that work just as well for home use.

So, consider an inexpensive model, or use a thatch rake for very small areas, to get the job done yourself with minimal hassle.

See Related:

• What is Verticutting?

• Best Power Rakes [Reviews]

• Top Benefits of Dethatching the Lawn

No, grass clippings left on your lawn after a weekly mow do not cause thatch. In fact, finely mulched grass clippings can be healthy for your yard by acting as a fertilizer that provides nutrients to your grass.

Say Goodbye to Thatch

No one wants a browning, disease-ridden yard. By regularly dethatching your grass and implementing good lawn maintenance practices, you will keep your lawn healthy and free from developing too much thatch.

From dethatching to aeration, find a local lawn care company to help you maintain your lawn. Lawn care professionals remove excessive thatch and deal with other lawn care chores to ensure your lawn will be the envy of your neighborhood.

Read More:

Main Photo Credit: pitrs / Adobe Stock