When the settlers arrived from Europe, they found grasses growing from sea to shining sea, a sight so wondrous that Katharine Lee Bates wrote about it in a poem that was turned into the anthem “America the Beautiful.” But all we seemed to have was that song, until recently, when people started asking, “Are native grasses right for my lawn?” Yes, native grass lawns are possible. We’ll explain how.

Native grasses were more than something wondrous to look at. They also protected the soil from erosion and degradation. Having evolved in the Americas, they needed no watering or fertilizing to thrive.

Native grasses went into decline as people moved in, bringing cattle and horses and a desire for crops they could eat and colorful things to look at. But some people are glad to celebrate their heritage, in ways big and small.

- What Are Native Plants?

- Advantages of Native Grasses

- Disadvantages of Native Grasses

- Warm-Season vs. Cool-Season Grasses

- Types of Native Grasses Good for Lawns

- 6 Steps to Establish a Native Grass Lawn

- Best Ornamental Native Grasses

- Cost of Installing Native Grasses

- Advantages of Professional Landscaping

- FAQs: Don’t Deplete the Wild

What Are Native Plants?

Native plants are those that were growing in an area before the European settlers arrived. They’ve lived here for hundreds or thousands of years and are well-adapted to whatever the local climate throws at them.

But is grass native to America as well? Luckily, yes: America has plenty of native grasses, which we will guide you through in this article.

Advantages of Native Grasses

American native grasses, like all native plants, offer several benefits, alone or in combination with wildflowers or other plants.

These are the advantages of having a native lawn:

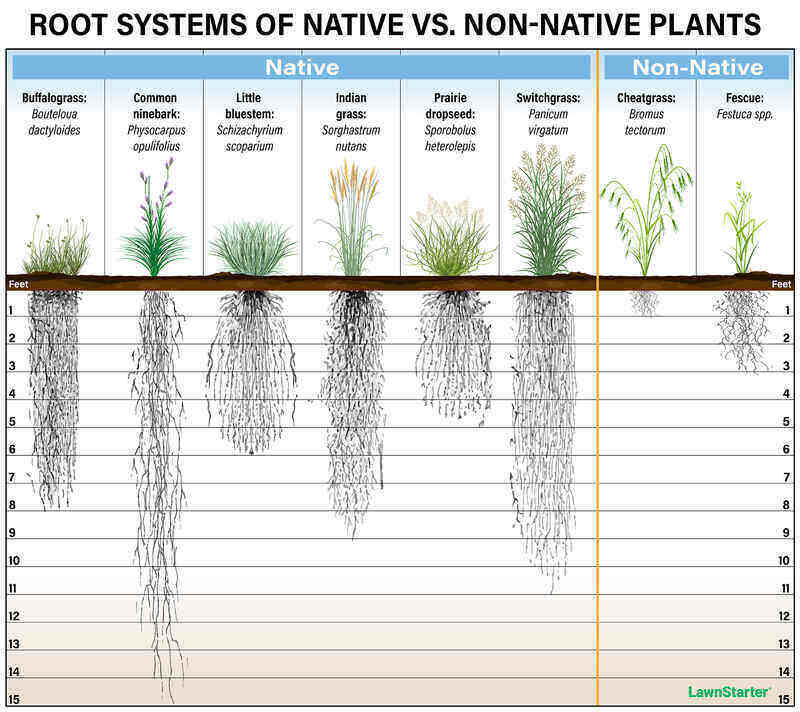

- Reduce soil erosion by having deeper, anchoring root systems

- Capture sediment being carried by water and wind

- Improve water quality by filtering chemicals and impurities from water before it flows into creeks and rivers

- Provide wildlife habitat, and attract birds that use them as a nesting place

- A source of pollen, seeds, and insects, it appeals to beneficial pollinators and can be a habitat for wildlife

- Drought tolerant, since their survival depended on their ability to consume less water

- Hardier than developed or imported grasses

- Most are perennials, requiring little maintenance

- Add height with a small footprint, if you want

- More resistant to pests, insects, and diseases than developed or imported grasses, which means less need for pesticides (which is good for your pocket and for the environment)

- Significantly fewer weeds because the leaf density provided up top denies them the sunlight they use to grow

- Take away carbon dioxide: One acre can store 1 ton of carbon dioxide per year, according to the University of Minnesota.

- Deeper root system will distribute carbon deeper into the ground and make the plant that much stronger. Almost 90 percent of non-native lawn grasses have roots no more than a few inches deep. Roots of native grasses go down several feet.

- Reduces greenhouse gas emissions of lawn mowing

- Eliminates cost of lawn mowing, from the price of a mower and its repair to the cost of its fuel (gas or electric) and parts (spark plugs, oil, blades)

Disadvantages of Native Grasses

Native grasses do have a few downsides to consider before you use them in your landscape:

- Will not grow in as thickly

- Will not be as green as a traditional lawn

- Doesn’t look like the lawn we see in movies and calendars

- Takes more effort: Native grasses are harder to establish as a lawn (and most aren’t suitable as a turfgrass alternative).

- Take longer to flower than developed plants, in some cases not flowering for several years

- Lower seed yields

- Some are ugly. Brown. Unkempt (the point of them is not to be trimmed or shaped). Some even have coarse, hairy leaves.

- Not showy, unlike the plants that were developed to be attractive

- Fewer choices of styles to plant than with developed lawn grasses

- A fire hazard: Native grass areas rarely remain green for an entire season. Once they turn brown, they burn easily. Keep them away from the house.

- Attract unwanted animals, such as rodents, voles, and snakes to your garden

Warm-Season vs. Cool-Season Grasses

Warm-season grasses and cool-season grasses have different attributes that depend on where the lawn grasses are native to, such as their respective growing seasons. Review the differences to know which is more appropriate for your home lawn:

| Warm-season Native Grasses | Cool-season Native Grasses | |

| Soil temperature for growth to begin | 60-65 F | 40-45 F |

| When they produce most of their biomass | In the hottest months of July to September, when air temps are 85-95 F | In the cooler air and soil temps of the spring and late fall, when air temps are 65-75 F |

| Out of season | Go dormant and turn brown in areas with a cold winter. | Require more water to stay green in a hot summer |

| Initial growth | Produce dense stands after 3 or more years | Produce dense stands in a year or two |

| Wildlife movement | Open ground between plants allows for nests and movement, and there is cover above | Plants grow too closely to allow easy wildlife movement or ground nests. Stems tend to turn down and become matted, taking away cover |

Additional source: Oregon State University

Types of Native Grasses Good for Lawns

While there are many types of native grasses available, not all of them are the best type to use to establish a lawn. Shortgrass does better than tallgrass if you want a prairie grass lawn that is kept mowed.

Choose whether you want to seed your lawn with a single native grass, or a blend of several. The increased demand for natural plants has spurred amazing research and development of new native blends that work well for creating lawns.

Caveat: While there are many advantages to establishing a lawn with native grass, there are some drawbacks versus using the standard “grass seed” we are all familiar with. Native grasses will not grow as thickly and may not provide the pristine, quintessential look of a traditional lawn.

With some initial investment of time and effort, though, you can establish a good native lawn that will save you trouble in the long run. Native lawn care is low maintenance since native grasses are more drought-tolerant, cost less money, and can still look good.

Pure Native Seed Types

- Buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides): The king of the native grasses. Native to a wide swath of America from North Dakota and Montana south to Texas and New Mexico. A warm-season native turfgrass suited for light traffic areas.

Short and slow-growing with low water requirements. Native seed mixes often use buffalograss as the base, with smaller volumes of other natives blended in.

- Sedges (Carex spp.): Popular bunching, glass-like plants that do well in light-use turf. Dozens of varieties handle a range of climates, soil types, and sun exposure. Pennsylvania sedge, Carex pensylvanica, (can you tell where this grass is native to?) is one variety gaining popularity as a lawn alternative in the eastern half of the U.S.

- Red fescue (Festuca rubra): A cool-season, sod-forming grass that can withstand heavy foot traffic. Also shade and drought tolerant. Already commonly used in “traditional” turfgrass seed mixes to increase overall shade tolerance so it can be grown in shade.

- Seashore bentgrass (Agrostis pallens): Cool-season, dark green turfgrass that withstands heavy traffic and low mowing heights. Native to West Coast states, but also found in pockets of Idaho, Montana and Nevada. Extremely drought tolerant.

- St. Augustinegrass (Stenotaphrum secundatum): Technically a native because early European explorers found it on the shores of Florida and the Gulf Coast, as well as the Caribbean and Western Africa.

However, turf growers have introduced it far outside its native coastal niche. It’s a warm-season perennial grass that grows in thick and dark green, handling heavy traffic, dense shade, and mild drought.

- Blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis): Another warm-season native that performs well in light-traffic areas. A low-growing grass that reaches perhaps 14 inches, known for its horizontal seed heads. Blue grama is an important forage plant widely used in native seed mixes with buffalograss. Tolerates low-nutrient soils, cold, heat, and moderate drought.

Blue grama is considered by professionals to be an excellent selection for rock gardens. It is also an excellent choice for informal areas calling for drought-tolerant grasses. If you have a lawn that will get only light foot traffic, you can use Blue grama as a turf grass, regularly mowing it to 2 inches high.

- Sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula): Warm-season bunchy or sod-forming perennial grass that is extremely drought tolerant and great on slopes for erosion control.

Seed Mixtures

- Habiturf: Warm-season seed mix developed for states in the Southwest and West. A blend of buffalograss, blue grama, and curly mesquite seeds. Habiturf establishes quickly and needs little resources, while staying soft to the touch.

- Native Mow-Free: Cool-season three fescue blend that can be maintained as turf or left unmowed (hence the name mow-free).

- No mow: Cool-season mix that grows in densely to handle heavy traffic and out-compete weeds. This no-mow mix is more drought-tolerant than traditional turf.

The above lists are nowhere near complete, as there are dozens of proprietary seed blends, and universities are developing new strains of natives at a speedy clip. Consult your local garden store or university Extension service to see what seeds or seed blends might work with your “untraditional” native lawn.

6 Steps to Establish a Native Grass Lawn

- Plan: Review the areas in your yard. Not all areas may be suitable for establishing native turf. In these sections, think about incorporating other native plants or ornamental bunch grasses.

- Assess the site: Test the soil to determine the pH, organic matter content, and overall soil type. Take a realistic look at sun exposure and drainage, making note of spots that are different from the main sections.

- Choose grass species: Determine if warm-season grasses or cool-season grasses are better suited for your climate and location and choose one that will thrive in your area.

- Prepare the soil: Remove existing vegetation with a sod cutter, a rototiller, or by using black plastic to smother out established grasses or plants. Till the top 6 to 8 inches of soil, amending it based on soil tests taken, and then level and smooth the tilled ground to create a uniform planting bed.

- Plant: Seed is the best option for large-scale areas, but you can also purchase grass plugs, or even rolled sod. Planting in the fall is ideal for most species because moist soil conditions and cooler temps allow for the root system to establish before winter. Early spring planting increases the risk of losing plants to summer heat.

- Maintain: Apply slow, light irrigation to keep soil moisture consistent and moderate. Cover seeds with a light layer of straw to keep them in place and provide protection from the sun. In the first year, mow at a higher height to reduce stress on the grass(es) while controlling annual weeds. In the second year, let native grasses grow until seed heads form to increase plant density.

Best Ornamental Native Grasses

If you’re more interested in native grasses for ornamental purposes, the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center selected these as “powerhouse grasses that are native far and wide across the U.S. and have great garden appeal”:

- Little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium): Little blue stems (hence the name) appear in August, growing to 3 feet by September. They turn an eye-catching reddish-bronze that will last all winter.

Little bluestem will tolerate sun or part shade and is easy to maintain, but self-seeds a good deal, so you might want to avoid it if your garden is small. Little bluestem attracts butterflies and nesting birds. It is a perennial that is native to more than half of the country, and is not to be confused with the big bluestem (Andropogon gerardi).

This is a warm-season grass.

- Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans): Livestock love this grass, which makes it one of the most critical grasses of the tallgrass prairie that once covered one-third of North America from Canada to Texas. Pioneers loved that it attracted songbirds.

Indian grass is striking in height (up to 8 feet) and crown (a foot-long, plume-like seed head). That golden crown contrasts nicely with blue-green stems when it begins to bloom in August. It drops a lot of seeds, making it better seen in a field than planted in your yard.

This is a warm-season grass.

- Prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis): It produces large, round clusters of leaves that curve outward. In summer, seed heads appear delicate as they grow several feet above the cluster. Come autumn, seeds drop to the ground from their hulls (hence the name).

Prairie dropseed is easily grown in dry soil in full sun. Some say the blooms smell like coriander, while others say they smell of… buttered popcorn.

This is a warm-season grass.

- Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum): Large, purple-red seed heads bloom in August. In fall, the stems turn yellow with orange tints. It does best in full sun; in shade, including the shade by a house, it is known to fall over.

Switchgrass is a popular choice to be placed along ponds or other water features in a yard or garden. It also can serve as a screen.

This is a warm-season grass.

- Inland sea oats (Chasmanthium latifolium): The name is derived from its large seed heads that look like oats as they dangle from branches. They sway in even the slightest of breezes.

Inland sea oats are ideal for that shady spot where you can spare some water. But be careful where you place it in a small garden; it can spread aggressively by rhizomes and seeds.

This is a warm-season grass.

- Blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis): A short grass, one that grows to perhaps 14 inches. It is known for its horizontal seed heads. But it can withstand drought, cold, and heat.

Blue grama is considered by professionals to be an excellent selection for rock gardens. Also an excellent choice for informal areas calling for drought-tolerant grasses. If you have a lawn that will get only light foot traffic, you can use Blue grama as a turf grass, regularly mowing it to 2 inches high.

This is a warm-season grass.

If you want to try a cool-season native grass, here’s a popular option:

- Bottlebrush grass (Elymus hystrix): This is a native grass that grows in bunches and does well in a lightly shaded area, such as near a house. It grows to 3 feet with pale green flower heads in summer that become spikelets of a straw color in the fall.

Bottlebrush Grass “is especially striking massed in front of trees,” according to the Master Gardeners of Northern Virginia.

Cost of Installing Native Grasses

If you are going to install native grasses from seed or plugs, look online or for a local seed supplier. Here is what you should expect to pay:

- A 1 lb. mix of bluestem, switchgrass, and Indiangrass is available for around $25. It should cover 500 sq. ft.

- A 1 lb. bag of Indiangrass seed is available for about $30.

- A tray of buffalograss plugs that should cover 70 sq. ft. is available for around $70. To cover 500 sq. ft., you would need 7 trays, which costs around $490. Buffalograss seed is also available.

To have a pro landscaper work on your project, here’s what you can expect to spend with professional landscaping costs:

- $5 per square foot for softscaping (putting in grasses and plants)

- $24 per square foot for hardscaping (making it a landscaping project by adding such things as pavers and ponds)

Most homeowners’ needs will fall somewhere in the middle, LawnStarter finds, so you might be best off using the average cost of $15 per square foot in estimating the cost of a project.

- For a large area, expect to pay $2,000 to $4,000 to have a professional install an acre of native grasses versus around $12,000 per acre for a traditionally sodded lawn.

If planting grass seed is a new endeavor for you, learn How to Plant Grass Seed in Six Steps before you start throwing down seed.

Advantages of Professional Landscaping

Adding native grasses to your yard or a landscaping project can be a fun DIY project. However, if you are going to add other elements (pavers, other plants, a pond) you should consider bringing in a local landscaping professional.

They will know:

- Where to properly acquire native grasses. And might have acquired seed from true native lands and used it to grow the plugs they make available, giving you the connection to your heritage you might be seeking.

- Which invasive species to avoid. There are a lot. For example, there is a list of 305 invasive grasses or grass-like plants (at least) that researchers have identified in North America.

- Which new invasive species are starting to appear. New ones are being identified every growing season.

- How to best place the native grasses. Trial and error can be fun, but for a large enough project, you might want to get it right the first time.

- How to mix them with wildflowers. Some native grasses will crowd out wildflowers and other native plants.

- They have specialized equipment and know how to operate it. As always.

FAQs: Don’t Deplete the Wild

Should you Go Out and Find Native Plants in the Wild?

No. Taking them will eventually deplete these areas of the seeds they need to be self-sustaining. Get your native grasses from a nursery. And if you look, you can find a nursery that gets the seeds it uses to grow its stock from the stewards of sites that protect native grasses.

What are Sedges?

Sedges are grass-like plants that are often confused with grasses. They resemble each other, but grasses are members of the Poaceae family, and sedges, which are smaller, belong to the Cyperaceae family. The stems of grasses are hollow and either round or flat. The stems of sedges are solid and triangular (leading to the saying, “Sedges have edges”).

Will Native Plants Attract Rats?

No. Natural plants do not provide the amount of food needed to sustain a colony of rats outside your home. Some small mammals (such as mice, gophers and moles) live in grassy areas, but are no more attracted to native grasses than other grasses.

Will Native Grasses Attract or Allow Mosquitoes to Breed?

Just the opposite. The use of native grasses takes away the standing water mosquitoes need to breed.

Call a Lawn Care Pro

Native grasses will fit into the climate and soil wherever you are, making it better, and will help to connect you to our heritage. You should try to add them, whether it is to a balcony garden, a small urban lot, an acre parcel, or a ranch. Review the points raised here, and then make your decision.

When you are ready to mow (if the grass requires it), contact a local landscape professional to keep your native lawn in top shape year-round.

LawnStarter participates in the Amazon Services LLC Associates, an affiliate advertising program. LawnStarter may earn revenue from products promoted in this article.

Main Image Credit: lostinfog / Flickr / CC BY-SA 2.0