Long before anyone ever set foot in what we call Virginia, it had native plants. These plants, like Joe-Pye weed and Eastern redbud, evolved to survive the area’s climate and help native animals and insects survive, too.

To do your part to help Virginia and its species thrive, here are 12 of the best Virginia native plants.

What are Native Plants?

Native plants have evolved and adapted to the local ecosystem over thousands of years, growing in North America way before the Europeans settled in the continent. Planting local Virginia native plants has many environmental benefits:

- Support more insects, birds, and animals than non-native plants

- Feed native wildlife and help maintain biodiversity

- Have adapted to local temperatures and rainfall

The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation and the Virginia Native Plant Society collaborate on the Native Plants for Conservation, Restoration, and Landscaping Project. This project is committed to protecting native plant habitats and species, given their importance to the ecosystem.

You can help the local environment as well by planting one (or more) of our selected Virginia native species in your yard. And the best part is that, besides being important for the environment, native plants present benefits for you as a homeowner and your lawn. Native plants:

- Don’t require as much maintenance as non-native plants

- Help save water

- Reduce soil erosion

- Provide a low-maintenance alternative to turfgrass

- Can offer you beauty for the entire year

Native Trees

Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida)

Both the official state tree and the state flower of Virginia, the flowering dogwood can be found across the state. It has pink, yellow, or white flowers, but their beautiful petals are actually bracts: modified leaves that look like petals.

The leaves turn red to reddish-purple in the fall, when the bright red fruits mature. Loved by birds and other wildlife, it is one of the best plants for sensory gardens.

Although a beautiful tree, flowering dogwood is not easy to grow. It is susceptible to anthracnose, a lethal fungal disease. Dogwoods can also be bedeviled by borers, cankers, and powdery mildew.

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 5-9

- Sun: Sun or partial shade

- Soil: Well-drained, average, acidic

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous

- Bloom time: Mid-April or May

- Water needs: Medium

- Mature size: 15 to 30 feet high, sometimes reaching up to 40 feet; 20 feet wide

- Potential hazards: According to the USDA, the berries are poisonous to humans.

Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis var. canadensis)

One of the first trees to bloom in spring, Eastern redbuds have rosy-purple, 1/2-inch flowers that bloom directly from the branches before the leaves come out. These flowers form tight clusters that sometimes fuse together, looking like little hummingbirds. The leaves turn yellow in the fall. Early settlers ate redbud blossoms on salads.

Native to the mountains and the Piedmont area, the Eastern redbud is easy to grow when transplanted at a smaller size. This tree grows fairly fast, approximately 7 to 10 feet in 5 or 6 years.

However, the Eastern redbuds have short lives, possibly living only 20 or so years due to their disease vulnerability. They are susceptible to Botryosphaeria canker and Verticillium wilt, both common types of tree fungus.

- Plant type: Tree

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 4-9

- Sun: Full sun or partial shade

- Soil: Any moist, well-draining, nutrient-rich soil

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous

- Bloom time: Early spring

- Water needs: Keep the soil moist to a depth of 2 to 3 inches. The watering schedule depends on your soil type, but you should water about once per week.

- Mature size: 20 to 30 feet tall with a 25- to 35-foot spread

- Potential hazards: Contains saponin, a toxin that is generally not absorbed by and passes through the body without issue.

White Oak (Quercus alba)

Living an average of 200 to 300 years, white oaks can live up to 600 years. In fact, the largest tree in the Commonwealth is located in Warfield, Virginia, and it’s thought to be 500 years old. White oaks don’t start producing acorns abundantly until they are around 50 years old. The acorns are loved by wildlife and can be eaten by humans, too, after being leached.

Young white oaks grow slowly, but they pick up their pace once their roots begin to spread. Because of those roots, which can become deep, the white oak is one of the best drought-tolerant trees to have, but only after it becomes well established.

- Plant type: Tree

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 3-9

- Sun: Full sun or partial sun

- Soil: Moist but well-drained clay, loamy, and sandy soils

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous

- Bloom time: Mid-spring, but don’t forget about the acorns in the fall

- Water needs: Low

- Mature size: 100 feet high, can be just as wide

- Potential hazards: Toxic to horses and has a low severity poison if eaten before the leaching process.

Native Vines

Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia)

The Virginia creeper is both a creeper and a climber, using its adhesive “disks” to cling to trees and structures. It can grow up to 60 feet long, and the adhesive disks can harm painted surfaces when pulled off. When used as a ground cover, Virginia creeper can also aid with erosion control and reaches about a foot high.

People sometimes mistake Virginia creeper for poison ivy because of the size of the leaves, but here’s how you can tell them apart: Virginia creeper has five leaflets, whereas poison ivy has only three. Just remember the rhyme: “Leaves of three let it be; leaves of five, let it thrive.”

- Plant type: Vine

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 3-9

- Sun: Full sun to part shade but will tolerate shade

- Soil: Moist, well-drained soils but will grow in drier soils and conditions

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous

- Bloom time: Leaflets turn bright red in autumn. Inconspicuous green flowers bloom in the spring.

- Water needs: Low

- Mature size: Plants and sap can cause contact dermatitis in sensitive people. It forms a blanket up to 12 inches high but can climb to 60 feet on trees or structures.

- Potential hazards: Seeds in the fruit may cause illness or may be lethal if eaten in large quantities.

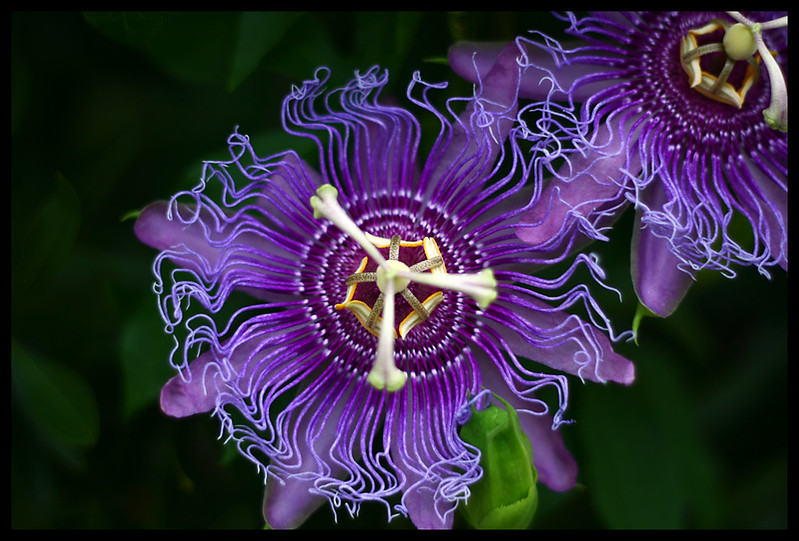

Purple Passionflower (Passiflora incarnata)

It’s the flower, as well as the fruit, that makes the purple passionflower unique. The 3-inch flowers have pale lavender leaves with fringe-like segments. The fruits, about the size of a small egg, have yellow-green skin.

The fruits are called maypops — and so is the plant — because of the loud popping sound made when someone steps on them. You might have heard this sound especially if you live in the counties of Northumberland and Lancaster or the regions of outer Piedmont and the southeastern coastal plain of Virginia.

Native American tribes used the purple passionflower as food, in drinks, and as medicine. Captain John Smith even remarked on this in his 1612 diary.

- Plant type: Vine

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 5-9

- Sun: Full sun or partial shade

- Soil: Fertile, well-drained soils but will grow in heavier clay soils

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous

- Bloom time: The beautiful flowers bloom from late May to August. The fruits ripen from July to October.

- Water needs: Low to moderate

- Mature size: Up to 25 feet long

- Potential hazards: None

Native Grasses

Bottlebrush (Elymus hystrix)

Green during the summer, bottlebrush grass turns tan, or rather the seed heads do. The seed head conveys this grass’s name; it looks like a baby bottle brush that is 2 to 6 inches long.

Bottlebrush grass remains green during the coldest of winters, making this native grass just right for your lawn if you live in the Piedmont area. It grows mostly in the spring under shade, even under deciduous trees. It provides cover for insects, birds, and small mammals.

- Plant type: Cool-season grass

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 5-9

- Sun: Sun, partial shade, shade. It is the most shade-tolerant native grass, making it one of the best grass seeds for Virginia.

- Soil: Well-drained clay, loam, or sand

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous

- Season of interest: Summer and fall

- Water needs: Low to medium

- Mature size: 2-4 feet high with a spread of 1 to 1 ½ feet

- Potential hazards: None

Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum)

Resistant to disease and pests, switchgrass is a native perennial that can be planted on slopes to control soil erosion. And if you like peacefulness, switchgrass is also a great tall ornamental grass to offer you some privacy.

Growing during the warm months, switchgrass becomes dormant during the colder months and can be cultivated in Southside and other parts of the state for grazing. Just be mindful that there are two switchgrass types: lowland varieties developed in more moist conditions and upland varieties suited to drought.

- Plant type: Warm-season grass

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 5a-9b

- Sun: Full sun, partial shade

- Soil: Sandy, loamy, clay, limestone-based

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous

- Season of interest: Summer and fall, but it also has winter interest

- Water needs: Medium

- Mature size: 3 to 6 feet

- Potential hazards: None

Native Shrubs

Common Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

Used medicinally by Native Americans, the common buttonbush has become familiar in native butterfly gardens, as shrub borders, and along pond shores and water gardens. Its 1 to 1 ½-inch flower has numerous creamy-white, tubular flowers packed closely together. The puffball flower looks like a pincushion.

Also known as button ball, button willow, honey-bells, and riverbush, the common buttonbush was introduced commercially in 1735 for beekeepers, who used it for pollen and nectar for honeybees. Native to practically all of Virginia, it is one of the first plants to produce springtime leaves. Songbirds, mallards, butterflies, moths, and hummingbirds also use it.

- Plant type: Shrub

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 5-10

- Sun: Full sun, partial shade

- Soil: Moderate to wet loam or sand

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous

- Bloom time: June to August

- Water needs: Average, high

- Mature size: 5 to 12 feet high and 12 to 18 feet wide

- Potential hazards: Common buttonbush contains a poison that, if ingested, can induce vomiting, paralysis, and convulsions.

Inkberry Holly (Ilex glabra)

The inkberry holly is native to the coastal region of Virginia. Although not ornamentally impressive, its black berries provide food for insects, birds, songbirds, opossums, and raccoons. When pollination occurs between male and female holly flowers, these pea-sized berries result in early fall. Female inkberry shrubs are common, but it can be difficult to find males.

The dark green leaves are spineless, flat, ovate to elliptic, and glossy with smooth margins and teeth near the apex. Unless temperatures fall way below zero, inkberry leaves usually remain attractive in winter.

Inkberry tends to be resistant to disease and pests, although its leaves turn yellow in high-pH soils and it may be prone to Phytophthora root rot.

- Plant type: Shrub

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 5-10

- Sun: Full sun and partial shade

- Soil: Clay, loam, sand

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Evergreen

- Bloom time: May to June, but the season of interest is during the fall, when the black inkberries become apparent.

- Water needs: Medium to high

- Mature size: 5 to 8 feet tall and wide

- Potential hazards: Ingestion of berries may cause diarrhea, vomiting, and other illnesses in humans.

Native Flowers

Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

Found in almost every county of the Commonwealth, the butterfly weed grows wild along the roadsides of Virginia. It spreads from the Coastal Plain to the Blue Ridge Parkway, also being found in the fields of southwest Virginia.

Also called chigger flower, orange milkweed, and pleurisy root, the butterfly weed is a milkweed species that produces large, flat to slightly domed 2- to 5-inch clusters of 25 or so bright orange star-shaped flowers from late spring through summer.

Although it has “weed” in its name, milkweeds are not weeds at all, but very important wildflowers. Milkweeds are host plants for the beautiful and endangered monarch butterfly. To help the monarch butterfly’s conservation, The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation urges citizens to conserve and plant milkweed.

- Plant type: Wildflower

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 3-9

- Sun: Full sun, light shade

- Soil: Prefers sandy soil but grows in almost any type of soil, including gravel or clay, as long as it is well-drained

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous or evergreen

- Bloom time: Mid-to-late summer

- Water needs: Low

- Mature size: ½ to 3 feet tall and wide

- Potential hazards: Butterfly weed can irritate the skin and eyes. Ingestion of small amounts can cause nausea, diarrhea, weakness, and confusion and large amounts can result in seizures, heart rhythm changes, respiratory paralysis, and death.

Blue Wild Indigo (Baptisia australis)

Native to most of Northern Virginia, except Prince William County, blue wild indigo is mostly found in the Piedmont and mountain regions of Virginia. Butterflies, honeybees, bumblebees, and other insects are fond of its blue-purple flowers, which bloom on a 14- to 16-inch upright spike.

Also called wild indigo and blue false indigo, blue wild indigo was once used by Native Americans as medicine and as a blue dye substitute for true indigo (Indigofera tinctoria). Other names for the blue wild indigo include rattleweed and rattlebush because shaking the mature 2 to 3-inch seed pods makes a rattling sound.

These seed pods appear green and turn black and can look pretty in dried flower arrangements. The blue wild indigo has no major diseases or insect problems and turns silvery-gray in autumn.

- Plant type: Wildflower

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 3-9

- Sun: Full sun

- Soil: Moist, well-drained clay but tolerates lime

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous

- Bloom time: Late spring to early summer

- Water needs: Medium

- Mature size: 3 to 5 feet tall by 3 to 5 feet wide

- Potential hazards: All parts are poisonous if ingested and cause nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Joe-Pye Weed (Eutrochium fistulosum)

Also known as trumpetweed and queen of the meadow, Joe-Pye weed blooms in early fall. Birds, bees, and butterflies are attracted to its flowers. Because they can become very tall, Joe-Pye weed needs to be placed at the rear of your garden.

Joe-Pye weed’s clouds of lavender blossoms can be an alternative to the butterfly bush, considered an invasive species in Northern Virginia (not to be confused with the common buttonbush or the butterfly weed, both mentioned previously in this list).

Named after a Mohican chief and healer – Joe-Pye was his Christian name – who lived in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, from 1740 to 1785, Joe-Pye weed can fall prey to powdery mildew, causing leaves to dry up and die but is otherwise relatively free of disease.

Pro Tip: Although the name may induce you to think so, this wildflower is also not a weed. Read our article on 13 Common Weeds in Virginia to learn more about the local obnoxious lawn-invaders.

- Plant type: Wildflower

- USDA Hardiness Zone: 4-10

- Sun: Full sun, partial shade

- Soil: Chalk, clay, loam, and sand

- Duration: Perennial

- Foliage: Deciduous

- Bloom time: From mid-summer into fall

- Water needs: Average to high

- Mature size: 4 to 7 feet high by 2 to 4 feet wide

- Potential hazards: None

How to Choose Native Plants for Your Virginia Landscape

Start with the USDA Hardiness Zones, which provide information, based on average annual minimum winter temperatures, about which plants will most likely thrive in a particular place. Virginia’s USDA Hardiness Zones range from 5b to 8b, or from −15 F to 20 F.

The Virginia Native Plant Society (VNPA) FAQs provide relevant information about what you can ask yourself before using any plant labeled “native” in your conservation landscaping:

- What is the source of this plant? Ensure that the plant originates from a nursery stock with responsibly collected seeds, plugs, and liners (plants grown from seeds or plugs to be sold when larger). Taking plants from the wild can severely damage the natural habitat and deplete plants in their natural environment.

- Is this plant native to my region? Ensure that the plant is native to Virginia, not just the United States. Plants labeled as “naturalized” can, in fact, be invasive to the Commonwealth.

- Was this plant grown from local stock or does the plant have a local origin? Ask whether the plant is from locally grown stock. Plants from local stocks grow better because they have evolved to withstand the local climate.

- Am I gardening close to a natural area? Is my planting for restoration? The genetics of plants that are not local to your particular planting area might affect the natural plant populations in ecosystems adjacent to your lawn or garden.

FAQ

Does an App Exist for Native Virginia Plants?

Why, yes. Yes, an app does exist for use as a native plant guide: The Flora of Virginia Mobile App from The Flora of Virginia Project includes:

- Photographs

- Botanical illustrations

- Information about rare or threatened plant species

- Color-coded county-by-county range maps

- Data about invasive plant species

The app costs $19.99 and is available for iOS and Android.

What Are Invasive Plants?

“Invasive plants are species intentionally or accidentally introduced by human activity into a region in which they did not evolve and cause harm to natural resources, economic activity or humans,” according to the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation.

Each plant’s invasiveness rank, or I-rank, is listed from high to low per its threat to native species, natural communities, or the economy in the Virginia Invasive Plant Species List. The ranking is available via PDF, an Excel spreadsheet, or a search-and-find database.

What Are Some Other Virginia Native Plants?

A few other plants native to the Commonwealth of Virginia include the following:

- Beebalm

- Black-eyed Susan

- Goldenrod

- Mountain laurel

- Rudbeckia coneflowers

- Wild bergamot

Where Can I Get Native Plants?

The website of the Virginia Native Plant Society (VNPS) details where, by region, to find native plants in their native plants list. The Society also provides a list of nurseries that carry native plants, as well as a list of native plant sales. You might also try your local nursery.

You can also purchase books detailing approximately 100 native plants by region from the VNPS. In fact, the Virginia native plant guides for the coastal plain were published by the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program with the help of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Call the Pros

Want to help preserve Virginia’s natural heritage? Looking for help with your native plants? Call a Virginia landscape professional near you. We have trusted lawn care pros in Richmond, Norfolk, Alexandria, Chesapeake, Newport News, and other areas around the Commonwealth.

Main Image Credit: Under the same moon… / Flickr / CC BY 2.0